Sale of oil assets is fueling Denmark’s green transition.

In another sign that the petroleum era is drawing to a close, Denmark is selling off its last oil company with barely a peep.

Once considered a strategic asset, on a par with national carriers or shipyards, the oil and gas division of A.P. Moller-Maersk A/S is being bought by French giant Total SA. The $7.45 billion deal is expected to be completed by 2018, pending regulatory approval.

Coming just three months after the sale of Dong Energy’s North Sea oil and gas production to German-based Ineos AG, Maersk’s move to offload its oil division has been welcomed by the government and trade unions alike. Even the nationalist Danish People’s Party, which supports the government in parliament, didn’t object.

The irony is that Denmark will need the income from oil and gas to finance its green transition and meet a pledge to stop using fossil fuels by 2050. That will mean keeping up production from the North Sea fields, which Total has promised to do.

“The more money they make on the North Sea, the more money there will be for us to spend on the green transition,’’ Energy Minister Lars Christian Lilleholt said in an interview in Copenhagen.

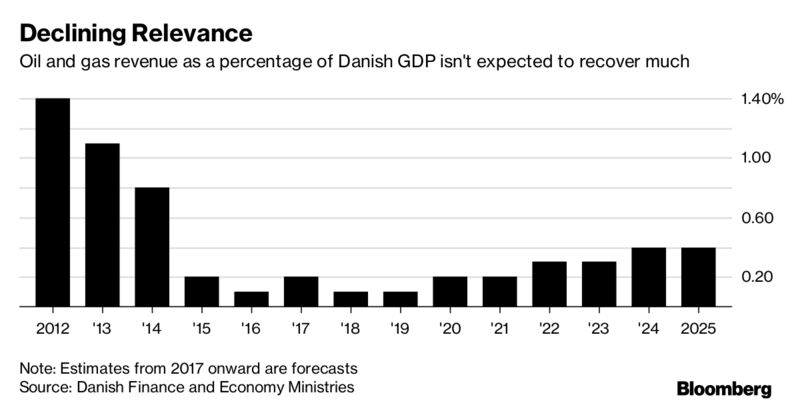

According to calculations by the Finance and Economy ministries, tax revenue from North Sea oil and gas has now fallen to a tenth of what it was at its height, only a decade ago.

The receipts from North Sea oil used to average about 8 billion kroner ($1.3 billion) per year. That would pay for about 1 gigawatt of new onshore wind capacity, which is sufficient to supply power to some 170,000 homes, based on a recent deal in Norway, according to Bloomberg Intelligence analyst James Evans.

Dong, a former state utility whose name is an acronym for Danish Oil and Natural Gas, is using at least some of the money it made from its divestment to build more offshore wind parks, expanding its dominance as the world’s biggest operator of sea-based wind turbines.

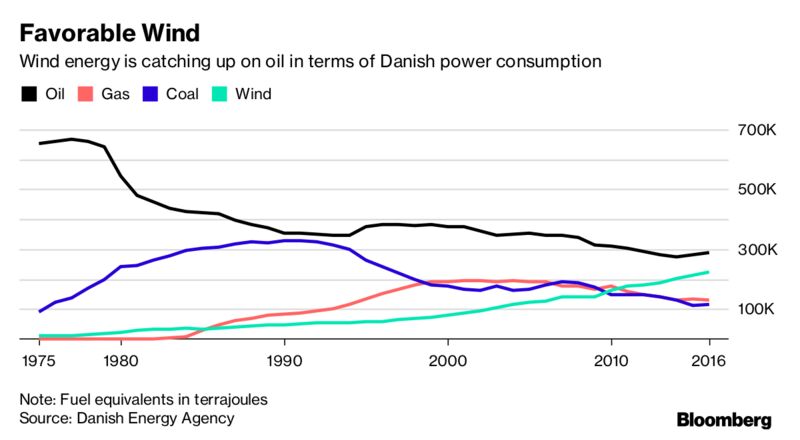

Denmark, which is also home to Vestas Wind Systems A/S (a company that produces more turbines than any other manufacturer on the planet), now gets more than 40 percent of its electricity needs from renewable sources, according to 2015 data, and aims to reach more than 50 percent by 2020. The country’s green sector already employs about 67,000 people, double the number of workers in its North Sea industry.

According to Peter Kurrild Klitgaard, a professor of political science at the University of Copenhagen, the reason behind the muted political response to Maersk’s sale is due to the fact that “there’s no energy crisis. We have more sources of energy than ever before.”

Paradoxically, Denmark got itself into oil exploration in the first place, back in 1962, because the founder of Maersk, Anders Peder Moeller, reportedlywanted to prevent German businesses from exploiting the country’s North Sea reserves. And it’s those very explorations, in often hazardous conditions, that have helped Denmark develop its thriving offshore wind energy business in the first place.

As Benny Engelbrecht, finance spokesman with the Social Democrats, points out, “Denmark’s green transition is based on our vast experience in offshore construction.”

Learn more here.