A rule of thumb in election years is that presidential candidates woo their political base with bold policies in primaries, then take the partisan edge off to court undecided voters in the fall.

From Bloomberg Green newsletter Oct. 26, 2020:

So why did Democratic candidate Joe Biden wait until general election season to introduce a $2 trillion climate plan that delighted his base?

“His plan today is far more ambitious now than it was in the primaries,” said Anthony Leiserowitz, director of the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. General elections these days are won by getting a candidate’s base out to vote, and climate change is energizing Democrats more than almost anything, Leiserowitz said.

“That is why he continues to talk about it, because he needs to mobilize young people. He needs to mobilize Hispanics, and he needs to mobilize suburban women, all of whom care more about climate change than others,” he said. “Never before in American political history” has climate change become a top voting issue for the base of one of America’s two parties, he said. He called Biden’s the most ambitious climate plan ever put forward by a general-election presidential candidate.

Polling about climate change helps explain why that’s happening. Research has found again and again that most Americans understand the basics of climate change and many would support policies to address it. Yet a false dichotomy between economic and environmental health persists in U.S. political rhetoric. One week before the election, it’s worth taking a look at whether such divisive political framing matches how Americans actually understand the climate problem.

After all, if climate change is still divisive, why would Biden be thumping it in his general election campaign?

Environmental protection has long been seen as a kind of luxury good. It’s great to protect endangered species we’ll never see, conserve lands we’ll never visit, and slash emissions for a future only our kids will know — as long as Americans can put food on the table and meet other basic needs like housing, health care and education.

This argument is what researchers would call a “testable hypothesis,” and 2020 has given them an opportunity to do just that. If the argument held, then when a terrible event occurs — say, a global pandemic that throws millions of people out of work while civic unrest rages over police violence — you would expect interest in climate change to plummet as day-to-day concerns overwhelm a nebulous, hard-to-grasp problem.

“What’s amazing is that we see literally none that,” said Jon Krosnick, a Stanford professor who has conducted public-opinion polls about climate change for more than 20 years. For his latest polls, “all of our data collection happened after the virus hit, after the economic crisis hit… There’s absolutely no evidence of any downturns in any of the wide array of climate-change related opinions that we looked at,” he said.

In fact, the opposite may be true. “In 2020, people are more sure than ever about whether temperatures will rise in the future,” Krosnick and his Stanford colleague Bo MacInnis wrote recently in an analysis of U.S. public opinions about climate change.

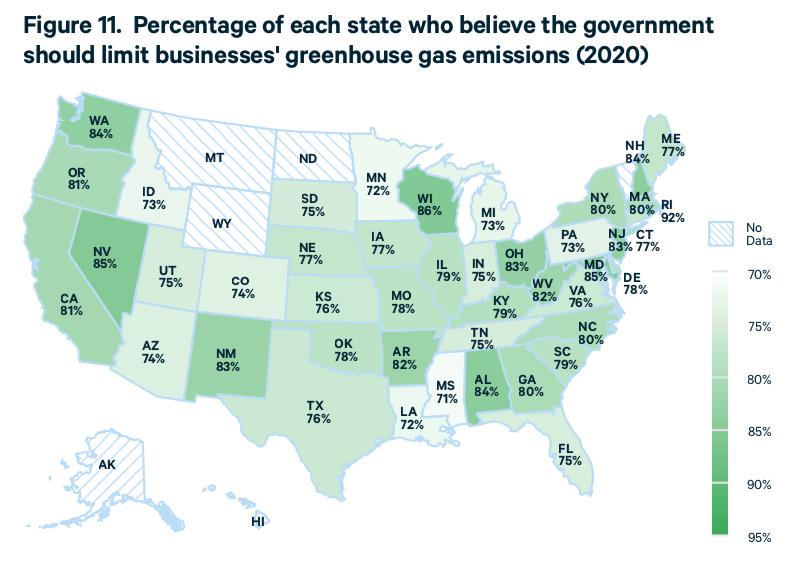

Resources for the Future, a Washington economic research group, Stanford University, and survey company ReconMR today published the latest analysis of recent polling, which found that clear majorities in all states (except for a few without data) favor federal action on climate change regardless of what other countries do. When asked whether the government should limit private-sector pollution, the numbers in support were very high.

Source: Resources for the Future

Public-opinion researchers often track not just the general citizenry, but also the intensely motivated sub-groups who obsess over particular issues. These “issue publics” are prepared to devote time, money, energy, and votes to a single issue, be it climate change, gun control, or reproductive freedom. “Each of these is a group of people who wake up in the morning, open their eyes, look across the pillow, and say, ‘Good morning, gun control. Another day, another opportunity for me to do something about you,’” Krosnick said.

For a long time, the climate change issue-public hovered between the low-to-mid teen percentages of the population, Krosnick said. But that figure has grown in recent years, reaching 25% in 2020 from just 9% 20 years ago. Abortion has had a higher engagement figure, reaching 31% in the 1990s.

What’s more, these issue publics are usually split equally on both sides — except when it comes to climate change. Among the most-engaged voters, about 90% want to take action to help solve the problem and only 10% are opposed.

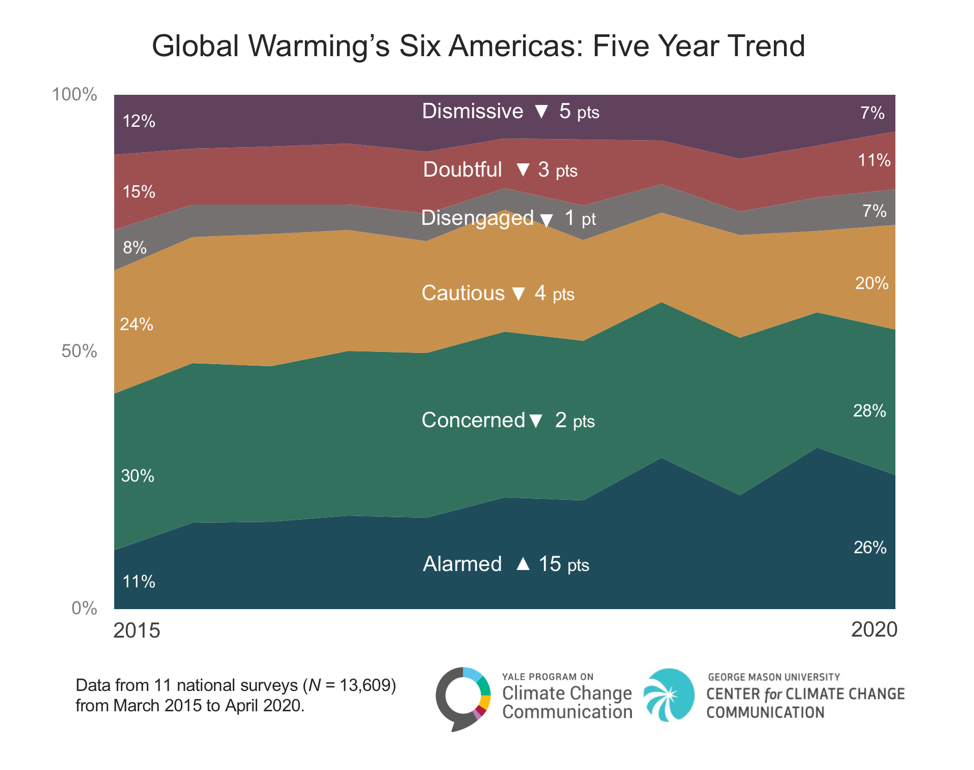

Since 2008, researchers at Yale and George Mason universities have tracked six perspectives Americans have about climate change, ranging from “dismissive to “alarmed.” In 2015, the percentage of Americans who were “alarmed” about global warming was roughly the same as those who were “dismissive” — 11% and 12% respectively. Today, the share of “alarmed” people has swelled to 26%, while the people who are “dismissive” has declined to 7%.

Source: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and George Mason Center for Climate Change Communication

There’s been a seismic shift in public opinion on climate change, with potential election-day implications. “This issue public leans so heavily on one side that for a candidate not to take a green position — even Republicans not to take a green position — is really forgoing votes,” Krosnick said. “This issue at this time in history offers a very special opportunity for candidates.”

See a great interview of Anthony Leiserowitz here.